I’ve often said that Persona 4 Golden is one of my favorite games of all time.

To say that now feels like speaking of an old friend you no longer call but still mention when conversations turn to nostalgia. See, when I say a game has made that leap—when I name it as one of my “all-time favorites”—it’s not just a compliment. It’s a quiet retirement, a place in my personal mythology, hung up like a portrait for everyone to witness. The game ceases to be questioned, no longer dissected, because its meaning isn’t open for debate. I’ve scored its greatness in permanent ink. It becomes a reflection of me, of my tastes—an artifact of self, curated and carefully placed under glass for others to interpret.

Persona 4 Golden is one of my favorite games of all time—so, go ahead, make your judgements.

I must say, even now, when I hold that PlayStation Vita in my hands and boot the game up, there’s a reluctance to question it, to reevaluate the title with fresh eyes. Every time a hint of critique begins to form, there’s a whisper in my mind, quiet but firm: “Come on. You told everyone you loved this.”

But do I now? Is it the game I’m so attached to, or is it something else entirely?

Maybe it's the memory of who I was the first time I played it—a younger me, open and eager, or so I tell myself. I know that one day, I’ll talk about the version of myself I am right now, in this moment, as if I were somehow more naive, more hopeful, than I probably am. As if life is nothing but the slow narrowing of one’s eyes, the steady hardening of one’s heart. Is that why the totemic memories decrease in frequency as we grow older—why they seem so much harder to hold on to?

Regardless, Persona 4 Golden got me at the right time. That memory is so sharp, so full of color and life. My memories of playing other games, in comparison, feel more like half-remembered dreams.

And that matters, doesn’t it? This game isn’t just a game—it’s a marker in my personal history, a touchstone that I feel obligated to preserve. A memory so significant it demands reverence.

Where do I begin?

2012.

My freshman year of college.

A time that, if I’m honest, was less a coming-of-age and more a rude awakening to The Way Things Are. There’s a story people sell you about going to university—something about freedom and limitless potential. I was supposed to feel lucky, combining the spaces in which I live and learn. Instead, I was quickly made to wade through crowds of people who dressed better than I did, and called each other names that made mine feel odd. They spent vacations at second and third family homes I would never visit, in places I had only ever heard of on television shows.

I remember vividly my first day on campus—a glimmering late-summer morning that made the brick pathways look polished, though they’d assuredly been worn smooth by generations of well-heeled shoes. I felt an urge to commit everything to memory: the wide sycamores, the nervous laughter, the cheap bulk pens from the orientation table that leaked ink on your fingers but gave you something to fidget with while strangers asked, "What’s your name?" and "Where are you from?"

I must have exchanged numbers with forty people that day, the names still needlessly taking up space in my phone’s contact list—Thomas, Jordan, someone who insisted I call him “Rico Suave.” I don’t think I texted any of them. But one moment lingers like the afterimage of a flashbulb.

I was talking to a guy whose name I’ve long forgotten—Michael? Andrew? Some placeholder name for a placeholder person. He looked like everyone else, except for the way his face lit up when I said mine.

“Steinberg?” he repeated, testing the syllables like a tightrope.

"Yeah," I said, and he leaned in. He leaned in like only men do with a question already forming behind his eyes.

"So, are you?" His voice dropped an octave, conspiratorial and amused, as if he were asking me if I had a fake ID or knew where to find weed. “You are, right?”

"Jewish?" I said it with a smile—an innocent, thoughtless thing.

I cringe when I think back on it now. There’s a strange kind of betrayal in your first moment of complicity, though it doesn’t feel like betrayal at the time. It feels harmless, maybe even generous. I thought I was giving him something—a thread of connection, an answer to his unspoken curiosity. But what I was really handing over was permission. Permission to make my name a puzzle piece, to pull it apart and reassemble it, to lay it flat on the table and decide what it meant.

Over the next four years at this private Catholic university, my name would come to reshape my identity in ways I couldn’t yet fathom.

Without any prompting on my part, people confessed to me, like a secret they couldn’t keep, that I was their first Jewish friend. At first, I laughed—what else was I supposed to do?—but the repetition of it wore me down. A professor, calling roll during the first semester, read out the full names for every other student but always stopped short at mine. “Jake,” she’d say, her voice soft and deliberate, as though she were skipping over something too sharp to say aloud. When I asked her about it, hoping for an innocent explanation, she gave me one that only deepened the sting: “I didn’t want to embarrass you.”

Moments like these—small, strange, and loaded—piled up in the background of my college life. They didn’t shout; they whispered. A friend at a play rehearsal complained it was “hotter than an oven in here,” and an Augustinian priest walking by called out with glee, “Don’t say ovens in front of him!” At a career fair, my advisor interrupted before I could say what my major was. “Business, right? Or Economics?” She didn’t wait for confirmation, she just barreled ahead.

The worst part wasn’t the moments themselves; it was how easily they became routine. I found myself smoothing over their rough edges with a laugh or a quick pivot, something to pull the attention away, to keep the air from thickening. I found my social identity became more and more steeped in Jewishness—thinking that, if I brought it up myself, it would protect me from others doing it on their own. It was a survival mechanism I didn’t know I’d developed until it was too late to stop. By the time I realized what was happening, it had already shaped the way I moved through the world.

Ohio? Really? Not New York?

I don’t reply, I just laugh.

I never know how these little anecdotes will land with other people. Do you nod and move on? Do you feel the edges of them, sharp and serrated, the way I do? I share them not because I want to linger in the telling but because I need you to see the shape of it—the small, persistent ways my identity seeps into the corners of my life.

There’s louder, more obvious stuff, of course. I would hope you don’t need me to talk about getting called a kike in a parking lot, the word slamming into my chest like the dull thud of a car door shutting too hard. Or about the girlfriend who dumped me after years together because her parents thought she’d ‘wasted enough time on a Jew.’ I would hope you don’t need me to spell out that anti-Semitism is bad and that it leaves marks—some faint and others deeper, the kind that don’t fade.

I often wonder what it would mean to cast off my last name, to lay it down like a burden I was never asked to carry. Would the world open up then? Would doors unlock without me needing to knock? Is it really that simple—a name stripped away, and with it, the weight of everything it signals? Is that all it would take?

Is that all it would take?

Is that all it would take?

Is that all it would take?

This identity has inflicted a lens so specific, so insistent, that it reshapes everything I see, touches every word I say. It has imposed upon me a perspective so singular that even when I want to tell you something as simple as why I love a video game, I can’t just say it. I have to wade through this first. I have to lay the groundwork, inundate you with context, hand you the dictionary to a language I wish I didn’t always have to translate.

How else could I explain how a game like Persona 4 Golden spoke to me, how it managed to hook into the raw, tender parts of who I was at that time? How else could I make you see what it means, how it feels, to carry this thing that colors even the smallest joys? To love something—a game, a story, an escape—and to know, always, that you’re bringing this whole history, this whole weight, with you into that love. That it’s not just about the game. It’s never just about the game.

I am starting up Persona 4 Golden again today, holding in me the person who held this same PlayStation Vita in 2012. What did this game see in him? Why do I remember, so vividly, nights curled up in my bed, in a dorm room too small, on a college campus too narrow, binging this game every night before going to sleep with the veracity one would attack a light, mildly interesting Netflix show?

I should recognize that the Vita itself was probably crucial at the time. Being handheld, it spared me from the awkward dance of negotiating TV time with my randomly assigned roommate—no need to hash out who got it when or how late I planned to stay up. Instead, I could slip into the smallest hours of the night, the soft glow of the screen and the squishy buttons providing the perfect amount of private company. I don’t even remember my roommate being there, in the background—though surely he was. That dick.

The screen lights up.

The music kicks in—jazzy, unexpected, a kind of playful melancholy.

Gamers are first tasked first with selecting their preferred difficulty level. Choosing between different permutations of vague, yet immediately understood, “Easy,” “Medium,” and “Hard,” options is a familiar pre-show ritual for any gamer. In its way, it’s comforting. It tells you the game is listening and your choices matter. Unlike TV or movies, a video game can’t proceed without you, and unlike books, it actively responds to your actions.

No matter the choice you make, the game greets you with a simple line of text: "Well, relax and have fun with the game."

At first glance, it’s nothing special. But there is something about that Well—a word that lands soft and familiar. Why is this omniscient voice taking on the tone of a friend preparing to tell a story? And then there’s the phrase “the game,” spoken with such certainty, as though it hasn’t already begun. But it has, hasn’t it? You’ve already picked it from the home screen, already pressed Start. Yet here it is, pretending otherwise.

This is what Persona 4 Golden does. Where other games begin with exposition, grand pronouncements, or the heavy hand of a tutorial, it begins with an invitation: relax, it says. Be at ease. There’s something almost audacious about it, asking for patience in a medium built on adrenaline and action. But it doesn’t care about that. This game knows what it is: long, slow, and dense with words. It knows that to play it, you will need something you may not even realize you possess—trust.

"Well, relax and have fun with the game."

I press X.

The screen turns to a cutscene: a limousine moves through a wall of fog so thick it seems less like weather and more like memory, or maybe forgetting. The vehicle is solid, defined, while the world around it feels half-formed, incomplete. Inside, everything glows in an ethereal blue—the upholstery, the crystal fixtures, even the air itself. A man sits across from you, strange and small, with features that stretch and bend as though his body belongs to a different reality entirely. His name is Igor, and he tells you this is a place “between dream and reality, mind and matter.”

This is how the game moves. It begins by speaking to you, the player, on your side of the screen. As if the curtain to the performance has yet to open, the game tells you to breathe before it begins. And now it pulls you further in—not yet into the game itself, but into the space that prepares you for it. The game knows where you are. It knows what it is. It knows that you cannot simply be thrown into its world; you have to be ushered. And so Igor, in his strange voice and stranger presence, asks you for your name—not yours exactly, but the one you will give to the story, the one you will inhabit.

Steinberg doesn’t fit.

Too many characters.

I step into the world of Persona 4 Golden as Jake Carson.

Just as I did in 2012.

Igor lays out tarot cards and asks if you believe in fortune-telling. “Each reading is done with the same cards, yet the result is always different,” he says. It’s a simple line, but like the fog, it holds layers. The cards are fixed—this game, these characters, these moments—but what you take from them, how you arrange them, will be yours alone. And then Igor laughs, his voice carrying something ancient, something true. “Life itself follows the same principles, doesn’t it?”

He isn’t looking for an answer. He’s offering an invitation. A quiet nudge toward introspection. This game is insisting that, though it wears the costume of distraction, it is not a place to escape. It is a place to reckon. To play this game is to enter into a dialogue—not just with the world it presents, but with yourself. To try, however imperfectly, to see through the fog.

I wonder if I grasped, even faintly, what Igor was asking of me. Or if I simply pressed X, watched the scene, and moved on.

“Each reading is done with the same cards, yet the result is always different. Life itself follows the same principles, doesn’t it?”

And now, I wonder what you, reader, make of this question. I want to argue with him. I want to tell him he's wrong. Not everyone has the same cards, Igor. Some people aren’t dealt the full deck. There’s no reshuffling for that, no second chances. Some people are born into a life where the deck is stacked against them, shaped by forces they had no say in, by circumstances they cannot escape. They don’t have the same possibilities. They don’t even play by the same rules.

Has Igor tricked me into getting emotional? Maybe. He said this was a place “between dream and reality, mind and matter,” but it’s hard to shake the feeling that maybe he’s speaking a truth that transcends this world. I tell myself now that, in this world, in this game, it’s as if everyone does get the same deck, and for a moment, there’s something strangely comforting about that, something that almost makes it all feel... fair.

Our next transition.

From the darkness.

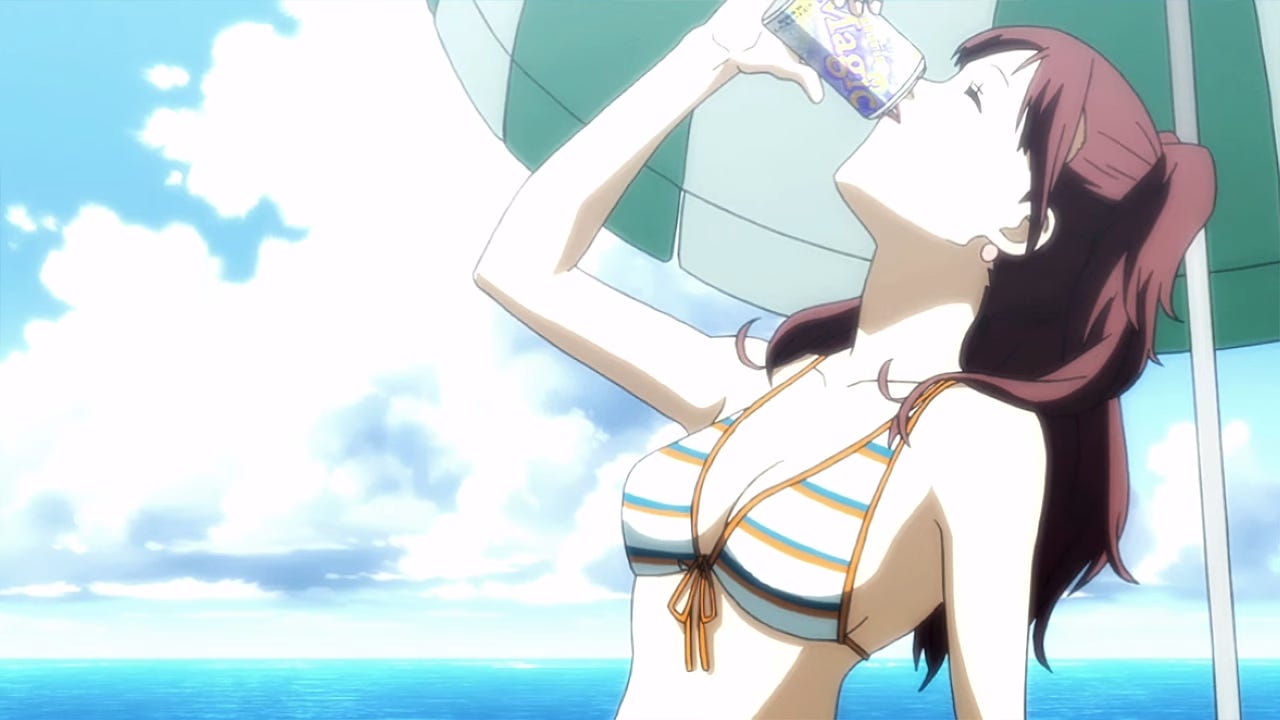

A bubbly soda pop commercial featuring a young, bikini-clad model smiling. The scene feels light, like an idealized version of life—polished, attractive, and designed purely for the audience’s consumption. Then, interruption.

We’re pulled into the world of news anchors discussing a scandal in which a politician is exposed for having an affair with a television host. We briefly brush up against the hard-edged reality of adult affairs, of consequences, and the politics that shape them. The scene zooms out, pulling back to reveal a group of Japanese business people, who, in their detached manner, discuss the affair in cold, pragmatic terms. “When you get down to it, financial and political clout is what matters,” one of them declares, a stark truth that slices through the earlier fantasy.

There’s storytelling in this movement.

We’re shown how easily a moment of idealism can be interrupted by the harshness of reality, and then, how that reality is colored by a world that values power, status, and influence over the things we’d like to believe. The game doesn’t let us settle into the fantasy for long. The youthful ideal versus the adult reality—this feels intentional. There’s a quiet insistence here that these truths are not incidental—they are the foundation of adulthood.

When I first stepped onto my college campus, I didn’t know to brace for impact. Was I supposed to? Was I meant to recognize, in that moment, that this was the line—the place where youth ends and something harder, colder, begins? I didn’t think of transitions like that. I thought they unfolded slowly, with time and warning, the way the seasons change. But what if they don’t? What if they arrive unannounced, not as a gentle breeze but as a gale-force wind that knocks the breath out of you? And worse—how many knew what awaited me and chose to stay silent?

Were others not wrestling with their own revelations? Were they not also learning, day by day, how cruel the world could be? Or was it just me, stumbling alone into the truth?

I fear I know the answer. So let’s move on.

I don’t want to get stuck here again.

We meet our protagonist on a busy train, surrounded by strangers, the whispers of his past cling to him. A memory surfaces: a teacher announces the protagonist's transfer to a new school. The classroom murmurs with disappointment, a faint acknowledgment of his presence. It’s a quiet moment, but it lingers, asking us to consider the weight of leaving and being left. Who was he before this train ride?

I focus so much on the life that followed, I occasionally forget to ask about who I was before I had gotten to college? I trace the outline of that question and find her—a girl I had already begun to drift from, though I knew she hadn’t yet let go. Her image lingers, like a photograph folded and unfolded too many times, the edges worn but the face still clear. A brunette memory that only returned in desperation. In quiet moments when the weight of the present was too much to bear.

Is that what this is? Some fleeting weakness or regret on a train ride?

The game doesn’t give us time to dwell. The narrative shifts, pulling us into a living room where a family watches television. Onscreen, a political affair unfolds, seemingly distant and impersonal. But nothing here is backdrop. These lives, this scandal, will entwine with ours before long. The world is pulling us in, layering the mundane with the ominous.

And then, just as we think we understand the shape of things, the memory shifts again. Something violent flickers in the periphery—disjointed, hazy, too painful to fully grasp. It’s gone before we can make sense of it, and we are thrust into the surreal intimacy of the Velvet Room. Here, the boundaries of reality bend, and we are asked to take it all in: the classroom, the train, the scandal, the violence, the fog. This is a world of connections, of unseen threads waiting to be revealed.

The sequence urges us to hold onto these details, to let them settle into the corners of our mind. Not everything is clear, but nothing is wasted. It is a story already in motion, and we are its newest passenger.

And then the game, at last, begins to stretch its legs. We emerge from the train station into a world of gray skies and muted colors, greeted by our uncle Dojima and his daughter, Nanako, a small girl whose quiet sweetness is immediately apparent. The conversation is clipped, practical, the way family reunions sometimes are when estrangement isn’t dramatic but mundane. Yet, for the first time, the game offers us a voice—a brief moment of choice in dialogue, a way to test how these characters might respond. We press a button, and for a fleeting second, we see the machinery of connection turn.

As we prepare to leave, a slip of paper falls from our protagonist’s hand, intercepted by a girl the game calls “Unfriendly-looking.” It’s a strange moniker, because nothing about her seems particularly unfriendly. I wonder how these assumptions may infiltrate and fill in our impressions of others. Am I more willing to see her as unfriendly because something outside of myself said she would be?

She hands over the paper with no more ceremony than handing back spare change, and yet, there’s something about her—something brittle in her stance, guarded but not cruel. The label is a riddle, a puzzle without pieces, and we can only wonder what the game wants us to see. A mystery to uncover later, maybe.

Then, a loading screen, and suddenly we’re in motion again, Dojima’s car winding into the heart of a small town like water through a narrow creek. We stop at a gas station, and the world pauses once more. Dojima notices the sharpness of a memory giving us pain and tells us to stretch our legs and get some air. This feels like a curious suggestion given that the game itself has barely drawn a breath. But as we step into the quiet of the town square, the first tremor of something larger ripples through—the protagonist’s headache, sharp and sudden, a reminder that something else is at work beneath the surface.

It’s a peculiar moment, this early pause. The game has only just begun, and already it pulls us aside, asks us to linger. And yet, as I think back, my own memory surfaces: “Well, relax and have fun with the game.”

Was this the echo the game wanted us to hear? A memory within a memory, folding in on itself like the edges of a paper crane. I wonder now if this break wasn’t meant to slow the story, but to remind us that stories are as much about the pauses as the motion—the space between, where everything else resides.

We wander the town, adrift in its rhythms. The voices of its occupants rise and fall around us, snippets of idle chatter that ripple like currents in a shallow stream. Some conversations pass unnoticed, their edges too faint to catch. But then, there is one that holds me.

Male Student: “Hey, do you know where my snack went? I had it in the fridge, but it’s gone...”

Female Student: “Oh, I ate it just now. I thought it was leftovers.”

Male Student: “What?! No, it wasn’t leftovers! I was saving it for later!”

Female Student: “Oh, really? Sorry about that.”

Later, in the game, I’ll find someone’s leftovers in the fridge. The choice will come—leave them, or eat them—and this moment in the town will rise to the surface of my mind like a stone skipped too far. I won’t eat the leftovers. Who would?

I pause the game. My mind is restless.

Why don’t I just eat the damn leftovers?

And deeper still: Why am I more generous to these digital ghosts than so many have been to me?

The answers rise unbidden, trailing shadows of memory. I think of the words that filled my chest as a young man, words sharp and weighty enough to crowd the air from my lungs. Words that stayed with me long after they were said.

Reader, I can not set them free for you, here. Instead, I will tell you what they did to me, how they filled my chest until there was no room for breath, no room for self, no room for kindness. And I will tell you what I have done with them: not cast them aside, not let them fade, but carried them forward, reshaped them into something I can live with, something I can own.

But, the echoes of that boy remain, faint but persistent. Sadder, meaner. I can still feel the hollow of that dorm room, the sound of laughter muffled through walls too thick to breach. I can still see my name on the lips of strangers, bent and reshaped into something it was never meant to be. Back then, I turned away from their voices and toward the screen. Toward Inaba. Toward its fictional shadows, which felt more honest and generous than my own.

But today, the game doesn’t speak to me as it once did. Now, I speak back. I see its questions—about belonging, about truth, about the ways we hold and betray each other—and I answer them differently. I am no longer the boy searching for shelter in someone else’s story. I am a man attempting to unravel my own.

And yet, those echoes linger. They hum beneath my skin, quieter now but still alive, like the afterimage of a lightning strike. They remind me of who I was—a boy aching for connection, trying to find himself in a world that told him he didn’t belong. They remind me of how much of that boy remains.

—

Thanks for reading all that.